The minimum wage is the starting hourly wage an employer can pay an employee for work. Currently, the federal minimum wage is $7.25 an hour (part of the Fair Labor Standards Act). Some states and cities have raised their minimum wage higher than that. In most instances, the higher of the prevailing minimum wage requirements is binding for employers.

Who earns the minimum wage?

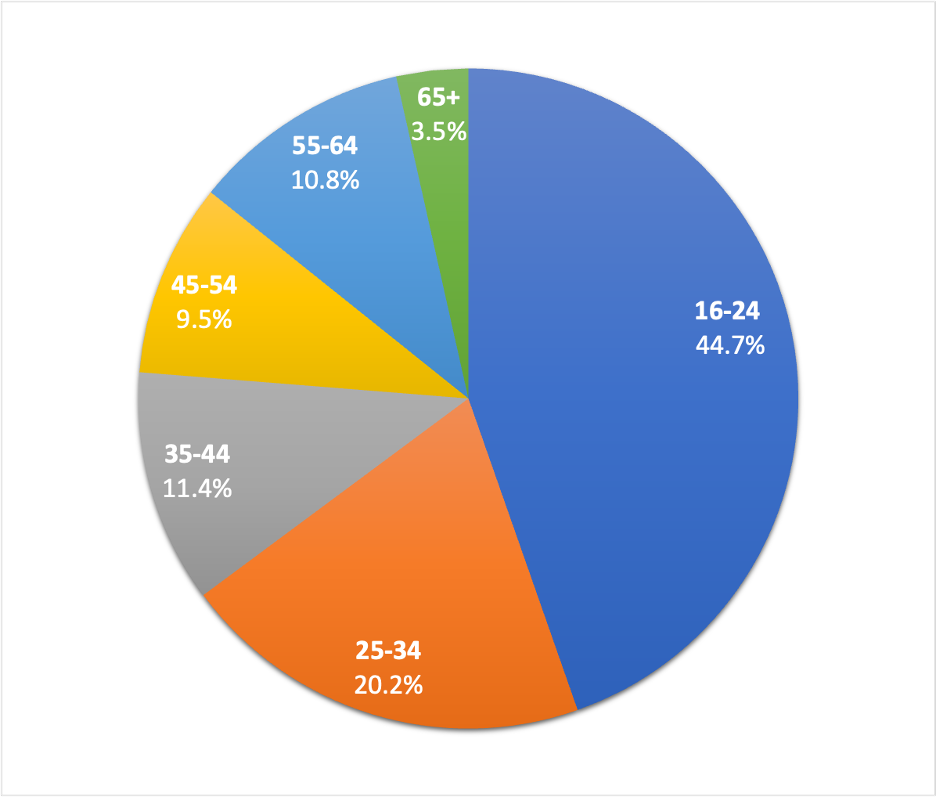

The latest report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) finds that 44.7% of all employees earning the federal minimum wage are between the ages of 16 to 24.

Proponents of a higher minimum wage often describe the age distribution of the minimum wage workforce using the proposed higher figure (e.g. $10.10, $12, or $15) instead of the current minimum wage. This has the effect of raising both the average and median age of a minimum wage worker.

Even among these older groups, the “typical” minimum wage beneficiary doesn’t fit certain popular perceptions. Using Congressional Budget Office (CBO) methodology, economists of Miami and Trinity University found that just one in 10 of those affected by a $12 minimum wage are single parents with children. A majority of those affected are either second or third-earners in households where the average family income exceeds $50,000 per year.

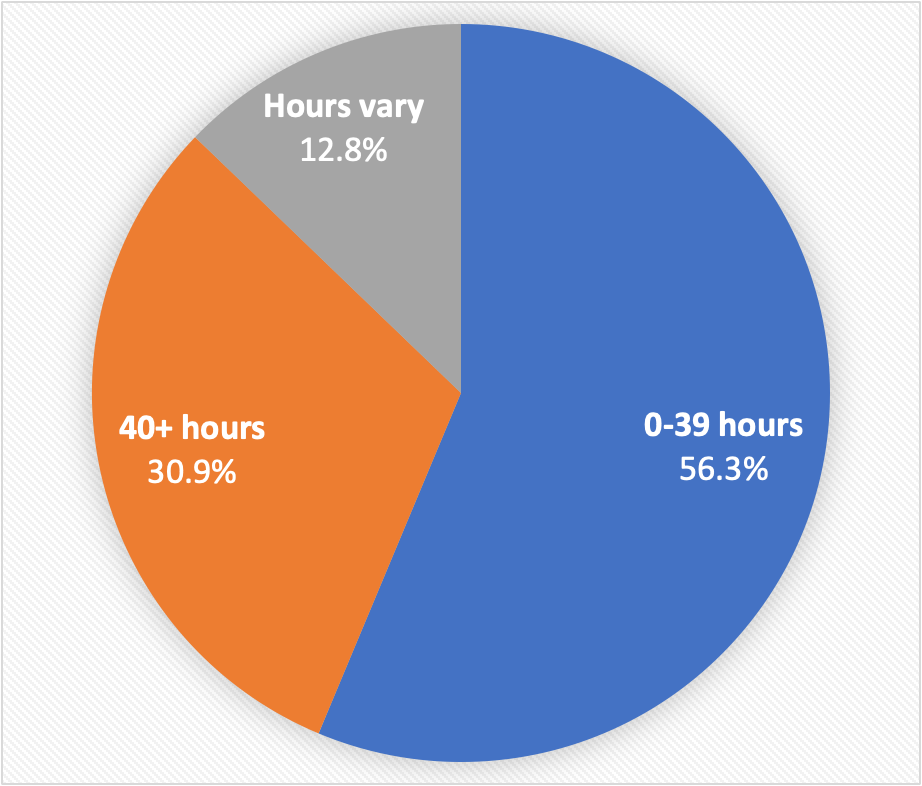

A majority of minimum wage earners are part time (56%).

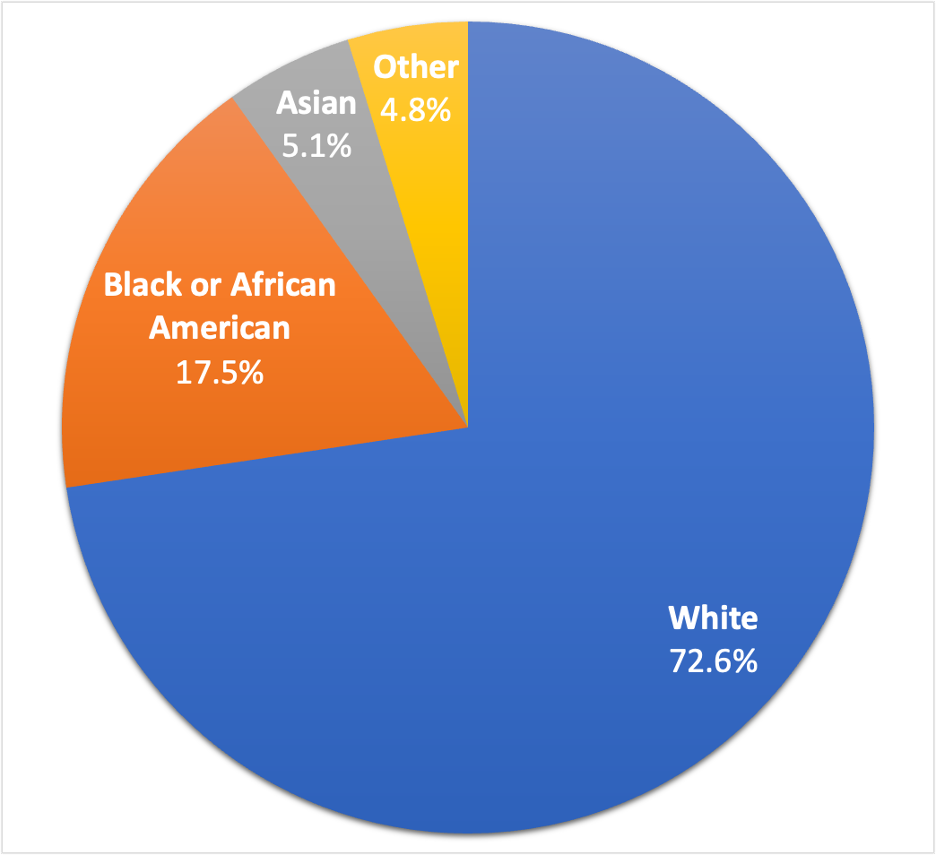

The BLS report finds that almost three quarters of minimum wage workers are white (72.6%), 17.5% are Black, and 5.1% are Asian.

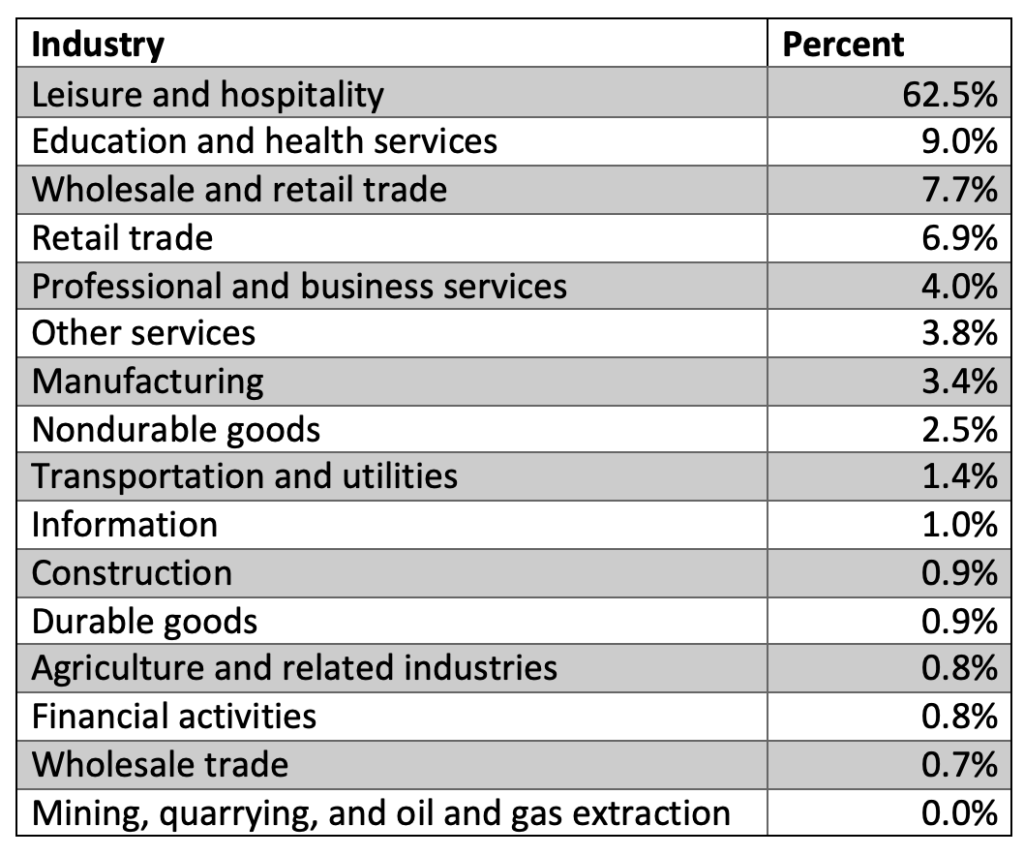

The report also shows the breakout of minimum wage workers by industry. The leisure and hospitality industry employs the most, encapsulating 62.5% of all minimum wage workers.

Do higher minimum wages lead to job loss?

Proponents say that boosting the minimum wage will reduce poverty without reducing jobs. But credible academic evidence shows otherwise: According to a 2007 summary of the minimum wage research authored by economists at the Federal Reserve Board and the University of California-Irvine, roughly 85 percent of the best research from the past two decades shows that a higher minimum wage reduces employment.

A December 2015 report from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco incorporated the most-current research, and concluded that, “[The] overall body of recent evidence suggests that the most credible conclusion is a higher minimum wage results in some job loss for the least-skilled workers…” According to the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office in 2019, a $15 minimum wage achieved by 2025 would cost the nation 1.3 million jobs, a $12 minimum wage in that time frame would cost 300,000 jobs, and a $10 minimum wage would cost 100,000 jobs.

Given the current economic outlook after COVID-19, economists’ follow-up analysis using this CBO methodology estimated that a $15 minimum wage by 2027 would cost the nation over 2 million minimum wage jobs.

How are employers adjusting to higher minimum wages?

Employers who utilize minimum wage labor typically operate on razor-thin profit margins. Raising labor costs forces these businesses to either raise prices, reduce employee job opportunities, or cut some of the services that they provide.

Perhaps the fastest growing consequence of a higher wage is the expedited shift to automation – replacing low-wage workers with technology. Andy Puzder, the former CEO of Carl’s Jr., explained, “If you’re making labor more expensive, and automation less expensive — this is not rocket science,”

In the past decade, we’ve seen Blockbuster replaced by Redbox and Netflix, parking and toll road attendants traded for self-service machines, rapid growth in the availability of self-service checkouts, and airport ticket agents working side by side with self-service check-in kiosks.

As of 2020, kiosks will be implemented at all U.S. McDonald’s locations. Other chains, such as fast casual-brands like Panera and casual-dining brands like Chili’s, have already begun to embrace automation that replaces tasks typically performed by employees. National chain White Castle has piloted a robotic fry cook in some of its restaurant locations.

Automation is not a new concept; self-service gas stations became a reality in the mid-1970’s. Artificially inflating labor costs will only hasten employers’ decisions to automate.

What do most economists think about $15?

A survey conducted by the University of New Hampshire Survey Center finds that nearly three-quarters of surveyed US-based economists oppose a federal minimum wage of $15.00 per hour. The majority believe a wage hike of this magnitude will have negative effects on youth employment levels (83 percent), adult employment levels (52 percent), and the number of jobs available (76 percent).

Prominent liberal economists who support a higher wage, including alumni of the Obama and Clinton administrations, oppose a federal wage hike of this magnitude.

The University of New Hampshire survey also finds that at lower levels (under $11.00 per hour) of proposed federal minimum wages, economists are divided largely by self-identified party identification as to an acceptable rate. The majority of Republicans and Independents who responded favored lower minimum wages ($7.50 per hour or less) and a number of Democrats who responded preferred a minimum wage between $10.00 and $10.50 per hour.

Does a study of fast food restaurants in New Jersey find that employment increases as a result of a higher minimum wage?

In 1994, Princeton economists David Card and Alan Krueger looked at New Jersey’s fast-food restaurants in the wake of the state’s 1992 minimum-wage hike—and found that employment increased relative to similar restaurants in bordering Pennsylvania counties. But six years later, the Card & Krueger study was refuted in the same economic journal that originally published it on account of serious data problems.

The problem stemmed from, among other things, a failure to properly define terms like “full time” and “part time,” or what constituted a regular hamburger. Survey researchers collecting the data pre and post wage hike reported numbers that suggested implausible swings in food prices and employment in less than a year’s time. Note the significant discrepancies in the table below: In some cases, a “regular” hamburger nearly doubles in price—in an industry where even a five percent price increase would be difficult to sustain.

A subsequent study that relied on payroll records rather than telephone survey data confirmed that employment did indeed decline following the minimum wage increase in New Jersey.

Does a higher minimum wage affect employment?

Yes, case studies show that raising minimum wage has a negative effect on employment.

After Seattle’s minimum wage was raised to $13 in 2016, researchers at the University of Washington found that hours worked by low-wage employees were reduced by 6-7%, and total payroll in such jobs declined despite the hourly wage increase, due to the decrease in hours worked. The study finds that the amount paid to low-wage workers decreased by $74 per month per job due to this minimum wage hike.

In San Francisco, another city that currently has a $15 minimum wage, as the minimum wage increased over time, each $1 increase correlated with a 14 percent increase in the probability that a median-rated restaurant would close, according to a study from Harvard Business School and Mathematica Policy Research. The authors noted that there was no significant impact of minimum wage increases on 5-star restaurants, suggesting that businesses already struggling to bring in customers may be most overwhelmed by minimum wage increases and be forced to lay off employees, and ultimately close, in order to cut losses.

Are there real stories that support the research findings?

Examples of the unintended consequences that accompany a higher wage can be seen in the states and cities that have implemented significant wage hikes. Many stories can be found at FacesOf15.com. Several examples are outlined below.

In December of 2017, New York City’s minimum wage rose from $11 to $13. Union Square’s iconic restaurant The Coffee Shop could not cope with the new mandate, and its 150 employees were forced to find work elsewhere when The Coffee Shop closed in October 2018. Co-Owner Charles Milite said that with the minimum wage going up, he could no longer afford to stay in business.10

In January of 2017, Maine initiated the first of its minimum wage increases which will hike the minimum hourly wage from $7.50 to $12 by 2021 – a 60 percent increase. Roger Wilday, business manager for nursing home Ledgeview Living Center, announced that they would be closing in October 2018 after 46 years of operations. Wilday said that the minimum wage increases were “the final straw.” When Ledgeview shuts down for good, its 72 residents and 122 staff members will have to relocate.

California has one of the highest minimum wages in the country ($11 as of January 2018), and is on track to be the first state to mandate a $15 minimum wage statewide in 2022. In San Diego, Cafe Chloe announced that with a series of minimum wage increases on the horizon, raising prices would no longer be enough to keep their doors open. Co-Founder Alison McGrath declared that the highly rated Cafe Chloe’s closure could signal“the end of mom and pop restaurants.”

Does raising the minimum wage reduce poverty or spending on government assistance?

Proponents of a higher wage often claim that a higher wage is necessary to eradicate poverty. Evidence suggests otherwise. Twenty-eight states raised their minimum wage between 2003 and 2007. Yet research from economists at Cornell and American University found no associated reduction in poverty. One of the factors that the authors identify is poor targeting: Census Bureau data show that over 60 percent of the poor don’t have a job, and thus can’t benefit from a higher wage.

Data from the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey was used to study the current working age population – 18 to 64-year-olds – living in poverty in each state. The analysis yields similar results; in 41 states and the District of Colombia, at least half of adults living in poverty are not employed and can’t benefit from a “raise.”

Another commonly-cited argument for raising the minimum wage is that it will reduce taxpayer spending on social programs. Dr. Joseph Sabia of San Diego State University and Thanh Tam Nguyen examined 35 years of government data across a number of different datasets and determined that, on net, minimum wage increases have little to no net effect on participation in–or spending on–a range of means-tested programs.

Has inflation eroded the minimum wage?

The vast majority of workers affected by minimum wage rates are employed in the service and retail industries. According to the 2015 Bureau of Labor Statistics report, the leisure and hospitality industry employs the highest percentage of minimum wage earners.

When the wage standard was first implemented in 1938, unskilled retail and service employees were not covered by the law. It was a minimum wage that covered mostly manufacturing, mining and transportation – it was a minimum skilled wage. But as Congress expanded the reach of the minimum wage law, the standard became irrelevant to skilled workers and became the minimum unskilled wage.

Proponents often argue that if the minimum wage had tracked inflation it would be far greater than the current rate of $7.25. But data from the Consumer Price Index suggests that, when adjusted for inflation, the 1938 federal minimum wage of 25 cents would have been $4.20 in 2015. The average inflation-adjusted value since 1938 is $7.40 an hour—or just 15 cents more than the current federal minimum wage.

If the minimum wage has substantial drawbacks, why are the majority of people for it?

A recent national poll commissioned by the Employment Policies Institute and conducted by ORC International (CNN’s pollster) found that nearly six in ten Americans supported a higher minimum wage. But – like most popular polls on the issue – these results are incomplete.

When informed of the unintended consequences that accompany that higher mandated wage, the results flipped. When respondents were informed that a $15 minimum wage would cause some less-skilled employees to lose their jobs, 52 percent opposed the policy. The opposition grew to 63 percent when respondents were informed that a $15 hourly minimum wage would cause some small businesses to close.

What’s the value of an entry level job?

Missing out on a job isn’t just hard in the short term— it’s detrimental to future career prospects for youth and the least skilled workers. Economists from the University of Virginia and Middle Tennessee State University found that young adults who worked part time in high school were earning 20 percent more six to nine years after graduation compared with their counterparts who didn’t find part-time work while in school. More troubling, an analysis from economists at Welch Consulting and the University of North Carolina found that teens who are unemployed today are more likely to be unemployed in the future.

Economists tied this benefit to the career experience that’s gained in an entry-level job — the “invisible curriculum” that teens pick up from reporting to a manager, interacting with customers and showing up to work on time. These are skills that teens don’t pick up in high school and often don’t have role models to mimic.

What are the alternatives to raising the minimum wage?

While the empirical research suggests that a higher minimum wage is an ineffective means to reduce poverty, there are more efficient alternatives. The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) has a proven track record.

A survey conducted by the University of New Hampshire found that the majority of surveyed economists (71 percent) believe that the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is a very efficient way to address the income needs of poor families. But only five percent believe a $15.00 per hour minimum wage would be very efficient.

Economists Joseph Sabia at San Diego State University and Robert Nielsen at the University of Georgia found a 1 percent drop in state poverty rates associated with each 1 percent increase in a state’s EITC. (The same study found no relationship between minimum wage hikes and poverty rates.)

How does the EITC work?

By targeting recipients through the tax code, the EITC supplements the income of low income households without creating additional burdens on employers. The credit constitutes a fixed percentage of earnings for each dollar earned up until the credit reaches the maximum. An earners’ maximum credit depends on several factors including earned income, marital status, and number of children.

The graph below illustrates the monetary impact the EITC has for a minimum wage worker who earns the federal minimum wage, depending on the number of children they have.

Is it time to end tipping?

In high wage markets, some full-service employers have experimented with eliminating tipping. By abolishing tips in favor of a 20 percent (or more) price increase or service charge, the restaurateur can redistribute money that was previously restricted to serving staff to help fund raises elsewhere.

But often times tipped employees have more to lose under the tipless system. San Francisco restaurants Trou Normand and Bar Agricole estimated they lost 70 percent of their wait staff during a tip-free experiment in 2015, despite the higher salaries. Owner Thad Vogler told CNN Money that his servers in San Francisco were making as much as $45 an hour with tips, and $20 to $35 an hour without.

This isn’t the only consequence: economists from Harvard Business School and Mathematica Policy Research, using data from Yelp, identified a 14 percent increase in Bay Area restaurant closures associated with each one-dollar increase in the base wage for tipped employees, which is equal to the regular minimum wage in San Francisco.

Thousands of servers in D.C., Michigan, Maine, San Francisco, and New York have vocally supported campaigns to save their tips. Most customers also favor the current tipping system. A recent survey of 3,000 U.S. consumers by Horizon Media found that a significant 81% prefer the status quo to a tip-free alternative.

Is the tipping system exploitative?

The tipping system is no different than a commission-based sales position. Tipped employees are guaranteed the same minimum wage as all other employees. And in reality, take-home wages for tipped employees are many times larger than their required hourly minimum. Census Bureau data show that tipped restaurant employees report earning over $13 per hour and top earners bring in $24 an hour of more.

Even in states where the base wage for tipped employees has been constant since the early 1990s, total take-home pay has increased in almost every year, as tip income has increased along with food and beverage prices.

Some advocates claim states that have changed their tipping system experience less sexual harassment. But data from the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, which tracks restaurant industry sexual harassment by state, shows that the percentage of harassment claims originating from the restaurant industry is nearly-identical in states without a tip credit as it is in those that follow the federal standard. In fact, a regression analysis that looked at all changes in the tipped wage over the past decade found a slight positive relationship between a higher tipped wage and the percentage of sexual harassment charges coming from restaurants. In other words, raising the tipped wage, if anything, may increase restaurant sexual harassment charges.